Summary

- Shale being promoted as an economic miracle

- It is claimed to have reduced US energy prices and carbon emissions

- In reality this has all been caused by the economic crisis

- Drop in demand reduced US coal and oil consumption by 10%

- Coal and oil redirected through world market to countries like China

- No world market for gas so US gas prices dropped instead

- Shale gas production costs are way above present prices, which must rise eventually

- Exploitation of shale is a sign of desperation

- Shale will only ever provide small amounts of expensive and dangerous energy

Both the promoters and detractors of shale gas (and oil) hold out the example of the United States, where it has seen its only widespread exploitation, as evidence of their positions. The negative consequences of shale gas extraction have been widely documented but here we shall turn our attention to the arguments used by those pushing the promise of ‘a shale-fueled economic miracle’. The people making these claims are far from restrained and are selling the hope that shale gas can solve all of the worlds economic problems. This attitude is extremely interesting in itself. No one in a position of power will admit that the economic crisis was triggered by the $140 per barrel plus spike in oil prices that preceded it, or that the stubborn failure of any real recovery to take hold has anything to do with the rise in oil prices over $100 per barrel, any time there is any hint of an increase in economic activity. However, the idea that a load of cheap new energy is what is needed to solve the world’s economic problems is a tacit admission that the lack of this cheap energy is what is actually causing the crisis. However these scraps of truth peep through from such a mountain of insane drivel for which there is no better poster child than the recent pronouncements of Lord Browne, the ex-CEO of BP, Managing Director of private equity firm Riverstone Holdings and Chairman of Cuadrilla Resources, on the infinite nature shale oil and gas.

The BBC reports, with a straight face, the deranged ravings of industry promoters about infinite amounts of shale oil and gas

The latest arguments that are being put forward to support this idea of a shale miracle are built on three ‘facts’. The first is that shale gas development has produced a glut of gas in the US that has pushed down natural gas prices. The second is that this glut of natural gas has caused a big switch away from the use of coal which has lowered the carbon dioxide emissions of the US. The third is that very large amounts of shale gas (and oil) are economically recoverable and so this situation can continue almost indefinitely into the future. All of these ‘facts’ are loosely based on some actual data but they have been so twisted and taken out of context in order to construct the overall argument that they do far more to obscure the actual truth than they do to enlighten. The extent to which the truth has been stretched to construct these ‘facts’ varies from plausible if you don’t think about it too hard, to the most insane drivel that could not possibly be true. Despite this there has been a recent spate of media stories hyping these ideas, doubtless pushed by various industry funded PR efforts. Back in the real world however, this readiness of certain people to lap up these ideas sheds more light on the psychology of those desperate for easy solutions to the world problems, than it does on the state we find ourselves in.

The idea that shale gas exploration has caused a glut of gas that has significantly lowered prices is the first of these issues. Natural gas prices in the US have certainly fallen in recent years and now stand at around $3 per thousand cubic feet (mcf). This is in the usual price range for most of the 1980s and 1990s. During the last decade however prices have spiked above $12/mcf at various points. Energy prices generally have fallen steeply since the start of the economic crisis. Oil peaked at $147 per barrel in 2008 before the crisis too but has since crept back up to the region of $100 per barrel. The fall can be explained by the fact that US oil consumption has dropped from over 20.6 million barrels per day in 2007 to around 18.7 million barrels per day in 2009 and has stayed close to that value since then. The subsequent recovery in the oil price is easily understood when you note that Chinese oil consumption has risen by around 2 million barrels per day in the intervening period wiping out that temporary drop in global demand caused by the drop in US consumption.

Comparison of US oil and natural gas prices over the last decade

To summarise, what has happened in the wake of the economic crisis is that oil and coal consumption in the US have both fallen by about 10 percent as a result of the reduction in demand for energy. Natural gas consumption on the other hand has risen slightly (by about 4 percent) since 2008 following an initial small drop (of around 2 percent) in 2009. This slight rise has been in response to an over 75 percent drop in natural gas prices. Part of the cause of this very different response to the crisis is easy to understand. There exists a world market for oil and coal that does not exist for natural gas. Unlike oil and coal natural gas can only be transported between continents if it is liquefied in massively expensive plants, transported in liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers (of which only a limited number exist) before being re-gasified in more massively expensive plants at the other end. All these expensive infrastructure requirements mean that sudden shifts in natural gas demand cannot be accommodated since much planning and investment is needed to make such changes if they are possible at all. Without any way of easily exporting gas for which there is no domestic demand prices must fall until either the demand reappears or the surplus production disappears, because it is no longer economic to produce the gas.

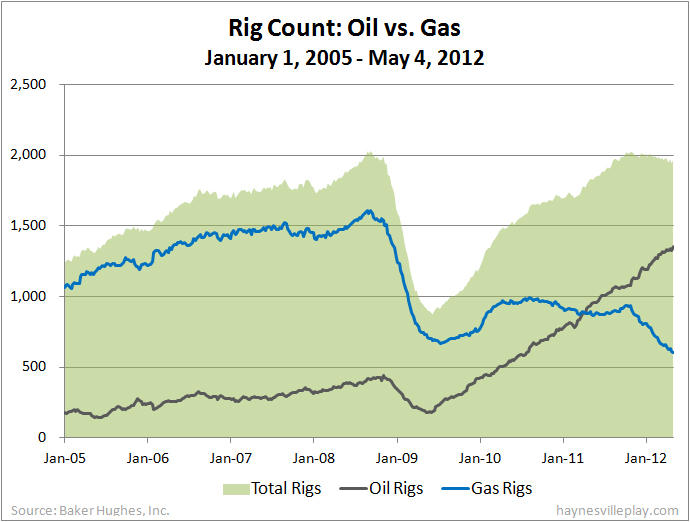

Here, is where the other major factor comes in. There is a significant overlap between oil and gas in terms of production, with a lot of gas coming out of oil wells and a lot of condensate (vapours of hydrocarbon liquids condensed out to produce liquids with the consistency of petrol/gasoline) coming out of gas wells. This means that a significant fraction of gas production is tied to oil/condensate production. In normal circumstances this fact is not of great importance but the aftermath of the economic crisis with energy demand in the US falling it took on a new significance. Over half of the oil that is used by the US is imported (a situation that will only change via reduction in consumption). The decline in US oil consumption has been matched by a decline in imports but as world demand has recovered (driven by China and other emerging economies) and prices have returned to the region of $100 per barrel there has been plenty of incentive not to lower domestic oil production. This in turn has worked to some extent to support gas production (even at very low gas prices) because the oil (or condensate) are often coming out of the same wells. Drilling rigs have been moving away from drier (less condensate-heavy) gas regions, like the Marcellus shale in Pennsylvania, to drill in oil or wet gas regions, like North Dakota and the Eagle Ford shale in Texas. However this has so far not translated into an immediate fall in gas production due to the long lead time before new drilling affects the type of active wells. Paradoxically the low gas prices and high oil prices are working through the link between oil and gas production, and the difference in there respective markets, to temporarily suppress gas prices.

.jpg)

US operating drilling rig counts for oil and natural gas drilling over last 7 years

However the more important number in the long term is not what the gas price is now but what it costs to extract the gas. Regardless of transitory effects mentioned above gas prices must eventually be determined by the production cost. There will be more of a time lag to sudden changes than for oil due to infrastructure difficulties but eventually they must filter through. Production costs for natural gas are constantly rising as conventional production declines and desperate efforts are made to find unconventional production to fill the gap (tight and shale gas etc.). While production costs are a moving target and accurate data is not readily available it is clear that the costs of shale gas production are not being covered by present natural gas prices. Data from both Wood Mackenzie and Goldman Sachs suggests that shale gas producers will lose money when prices are below $6-8 per mcf (compared to the present price of around $3 per mcf) and this is confirmed by their present financial difficulties. These high costs will only increase with time as lower cost resources are exhausted. The present low price of natural gas has very little to do with shale production and everything to do with the economic crisis, and in the long term the increasing use of shale gas (if possible) would guarantee that gas prices would need to rise much higher because of the high costs of extracting the gas.

Natural gas price necessary for extraction to be profitable in various shale plays in the US (most plays unprofitable at present prices)

The second issue that needs addressing is the idea that shale gas exploitation has caused a drop in US carbon emissions by lowering natural gas prices and causing a switch away from coal to gas for electricity generation. US electricity generation fell from 4.1 billion MWh in 2008 to 3.9 billion MWh in 2009 but has since recovered 4.1 billion MWh in 2011. US coal consumption for electricity generation, its main use, was 1.04 billion tons in 2008 before the onset of the economic crisis but fell to 0.93 billion tons in 2009 and was still at the same value in 2011. In the same period natural gas usage for electricity generation has risen from 6.6 tcf in 2008 to 7.6 tcf in 2011. We have already seen that the idea that shale gas production (rather than the economic crisis) is the cause of the low prices, is not supported by the evidence. A large part of the drop in US carbon dioxide emissions is not even due to changes in the balance of fuels used for electricity generation. The 10 percent drop in US oil consumption (which is mostly used for transport fuel) is responsible for a large part of this emissions decline. Changes in fuels used for electricity generation are also significant but like the fall in oil consumption this has been driven by the economic crisis not shale gas production. All this also ignores the fact that fugitive emissions of methane mean that natural gas is the same or worse than coal in terms of its impact on the climate.

Finally the third issue is the assumption that because shale gas production is increasing at present, it will continue to do so and that it will provide a major (and cheap) energy source for decades to come. We have seen that shale gas production is extremely expensive and it is generally not profitable to extract at current or historic gas prices. It was only during the run up to the economic crisis when gas prices were sky high that shale gas drilling really took off. Even if prices rise back to those levels, shale gas appears to be depleting very fast. Individual shale gas wells can see production declines of over 80 percent in the first year and new wells have to be constantly drilled in order to maintain production. These drilling and fracking costs not only dominate the economics of shale gas but also place fundamental limits on the rate of production. For conventional oil and gas drilling, bringing new production on stream is a cumulative process which adds to the total production, at least for a significant period of time. For unconventional gas however the steep decline in production from new wells means that total production is mostly determined by the number of new wells drilled per year rather than the sum of total wells drilled in the recent past. Production is therefore severely constrained by the number of drilling rigs, other equipment and trained workers available to drill and frack wells. There are also a number of questions about whether operators are being far too optimistic about how much gas their wells will ultimately produce.

Average well production curve (blue) for the Haynesville Shale along with the cumulative production from the well (red)

At a larger scale shale plays typically have quite variable geology with certain sweet spots providing most of the gas produced. In other areas outside these core regions while there may be shale gas there, it is not possible to get large amounts out of the ground. The Barnett shale, the first area to be extensively exploited for shale gas in the US, covers 24 counties in Texas but only around 6 of those counties have seen significant gas production. Drilling rig counts in the Barnett shale were beginning to decline even before the economic crisis began as companies shifted focus to newer shale plays with more drilling opportunities such as the Haynesville in Louisiana and the Marcellus in Pennsylvania. Since the Barnett shale has only been producing significant amounts of gas for less than a decade, the fact that the industry is already moving on to greener pastures does not bode well for the longevity of shale gas production. While increasingly the media echo the most wild and unsupported assertions of industry figures regarding the potential of shale gas, even the official industry figures do not support these levels of optimism. The Potential Gas Committee 2008 report estimated that there is 441 trillion cubic feet (tcf) of technically recoverable shale gas resources in the US, of which 147 tcf have a greater than 50 percent chance of being possible to extract. Given that US gas consumption is about 24 tcf per year this translates into only 6 years worth of gas. However, even if this number is not grossly over optimistic the gas would only be economic to extract only if gas prices were very high, which is not the case at present.

Shale gas production in the US by area (Production from Barnett Shale has plateaued since 2009)

Another unconventional gas source, coal bed methane, for which significant development began earlier than shale gas, appears to have already peaked and production has been declining in recent years. Meanwhile the recent overly optimistic predictions of how much shale can be extracted are crumbling before hard economic and geologic realities. Despite all this, the unrelenting hype around shale gas has if anything got even more extreme even as the evidence has mounted against it. This is not hard to understand since with companies making little or no money from the exploitation of these resources their only source of funds is investment. Shale gas is a classic bubble, where the underlying worth of what is being sold is largely irrelevant and all that matters is what the perceived future worth will be. As with all such bubbles they can only be sustained as long as that perception is maintained and this requires a constant stream of hype to support those perceptions. With resource bubbles it is usually those who provide services and equipment (providing picks and shovels, and running brothels in the case of the gold rushes of the past) that will profit regardless of whether the extraction is profitable overall, and have a particular incentive to promote the bubble. This is not to say that the production of some shale gas will not be profitable after prices adjust above production costs or that large amounts of social and environmental damage will not be caused by investment driven drilling that is unlikely to ever turn a profit. In the end though the wild fantasies of vast amounts of cheap and profitable shale gas are a contradiction in terms.

The real picture we are faced with is one in which the depletion of energy sources is the driving force. This has caused not only the present economic crisis but the rush to exploit more extreme energy extraction methods. Both of these effects are mediated by the mechanism of higher energy prices. While these market mechanisms can result in wild swings in prices (typical boom and bust behaviour) the long term trends are set in stone. Energy will continue to become more difficult to extract as more easily accessed resources deplete and hence more costly in the long term. In general the effort involved in energy extraction is also highly correlated with the amount of environmental damage caused. So as the effort involved increases the environmental impacts (and the toll taken on local communities) will also increase. As long as the driving force behind our societies is more, more and more energy, it will inevitably mean that energy must become more extreme, dangerous and expensive. All the less dangerous and cheaper to extract energy sources are already being exploited. The only thing that allows the sort of hype we are seeing around shale gas is a staggering disconnect with reality, which denies the essential nature of the energy predicament we face. Shale was too difficult and expensive to be worth large scale extraction efforts a little more than a decade ago and what has changed is not that reality but the level of desperation as existing energy production has declined.